Summit Tunnel

Before the railway arrived the local landowner, Abraham Chadwick, operated a quarry at Sladen Wood adjacent to the Turnpike Road which possibly eased the initial work prior to digging the tunnel. Preliminary work on the 1 mile 1,125 yds long tunnel commenced in late 1837

Summit Tunnel Fire

The fire occurred on the 20th December 1984 when a train of thirteen petrol tankers hauled by locomotive 47 125 was passing through the tunnel. One-third of the way through the 4th tanker derailed which resulted in the derailment of the following tankers. Only the locomotive and the first three tankers remained on the rails. One of the derailed tankers fell on its side and began to leak petrol and the vapours ignited probably due to Hot (axle) Box. Quick action by the 3 crew members enabled the train to be divided with the loco and 3 tankers removed to safety and the Emergency services called. The tunnel closed for the first eight months of 1985 during which time Littleborough was served by a shuttle service from Rochdale. Restoration involved relining a section of the tunnel, including the use of rock bolts to secure the walls, and replacing 550 yards (500 m) of track and sleepers. Before it re-opened to traffic on 19 August 1985 the public were allowed to take part in a celebration walk through the tunnel to mark the reopening.

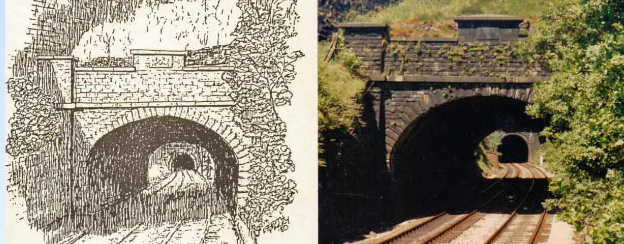

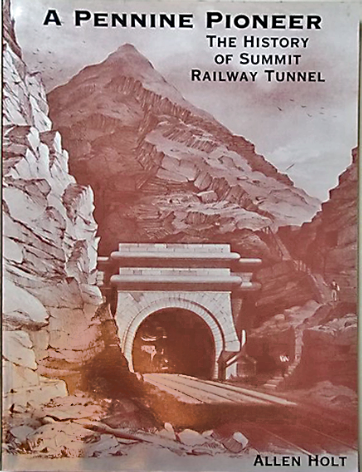

For more information on constructing the tunnel see ‘A Pennine Pioneer ‘by Allen Holt (George Kelsall, 1999) (left) and novel ‘The World From Rough Stones’ by Malcolm MacDonald (Random House, 1975).

In 1843 there was a collision in the tunnel and no doubt there were other incidents but the biggest was the 1984 fire. Other matters over the years includes when parts of the tunnel were relined in October 1936 and circa 1939 when soldiers were guarding

Construction work proper stated during February 1838. Some 15 shafts were sunk (alternative sources suggest 14) of which 12 remain open. By September 1838 over 3,000 construction workers were involved ensuring a work-rate of 85 yds in first month & 200 yds thereafter. A Dr Barker was surgeon to the Summit Tunnel Sick Club, formed by the employees as a form of insurance scheme. The tunnel was completed in September 1840 and after remedial works it officially opened on March 1st, 1841. It cost 41 lives and over £250,000.

Summit Tunnel. On 28 December 2010, the first passenger train from Manchester to Leeds was derailed when it struck fallen ice built up over the Christmas shut-down.and later thawed.

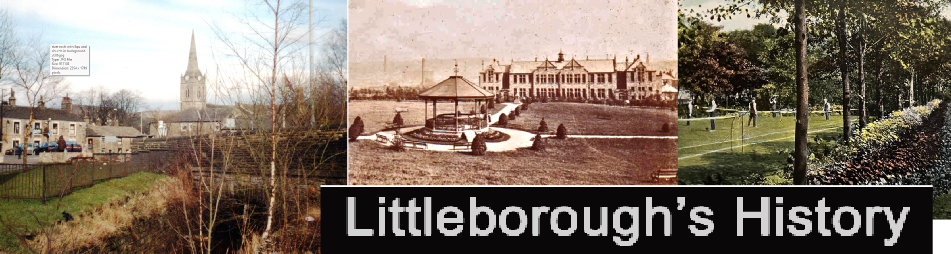

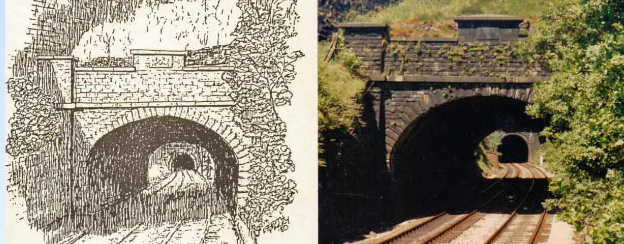

The west end of Summit Tunnel, was listed on 23rd April 1986 as it contained the only known example of the Coat of Arms of the Manchester and Leeds Railway. Pictured above right .